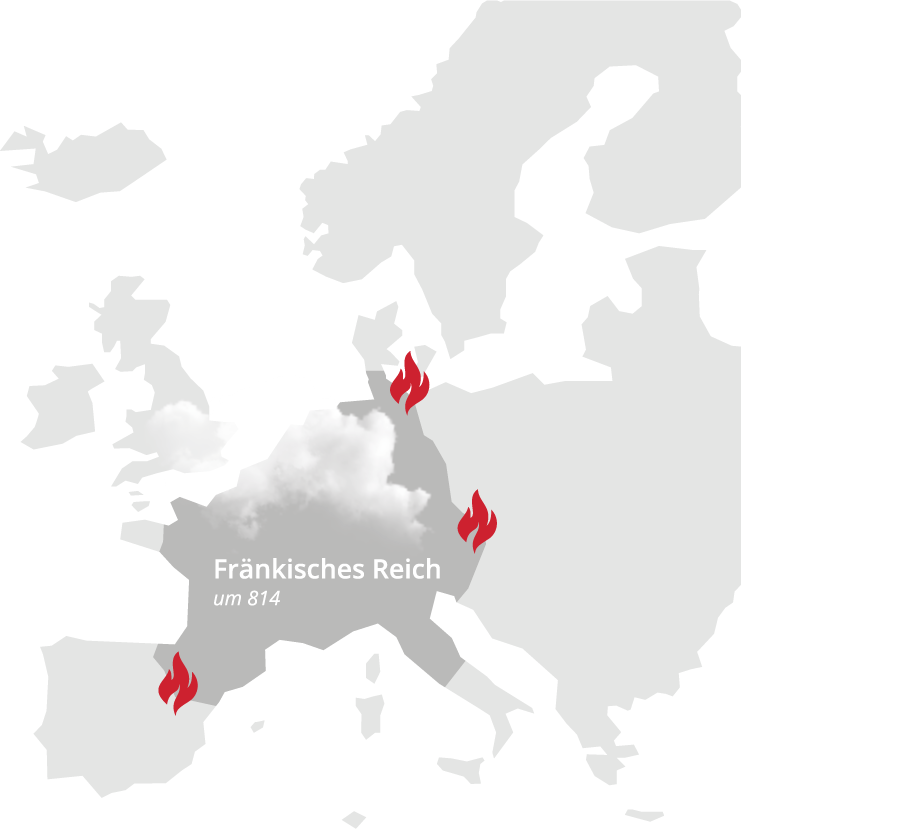

When Charlemagne died in January, 814 he left his son and successor, Louis the Pious, an empire whose borders stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to today's Czech Republic, south to central Italy and north to the coast of the North Sea. Charlemagne’s reign was marked by wars, but also by the Carolingian reforms, which allowed culture to flourish throughout the Frankish Empire. Louis the Pious continued his father's policies after his death. With great enthusiasm, he directed his political action toward ensuring that everyone within the kingdom knew what their social position was and what role they were to fill in society. The argument for such policies was that if God was content with the people in the Frankish Empire and their way of life, then everyone would flourish and the kingdom would prosper.

A Search for Order

in the Frankish Empire

Threats from Extreme Weather Conditions

Severe weather as a

form of divine punishment?

But it seemed that God did not honor such efforts: beginning in 820, catastrophic weather conditions set that threatened the Frankish Empire’s very existence for several years. The kingdom was beset with periods of heavy rains, floods, icy winters, and droughts, which created insurmountable obstacles for the people. Technical aids, the proper storage of foods, and medical knowledge were rare, and many were unable to survive the hunger and disease that immediately followed the severe weather. But, this does not mean that the people of the ninth century did not contemplate the causes of the severe weather, nor that they did not take action to try and change their situation.

What threatens us?

Heavy rains and floods, bitter cold and relentless droughts, epidemics among people and livestock, crop failures and hunger – the list of catastrophes that struck the Frankish Empire between the 820 and 824 is long and seemingly unending. Today, we know that much of the extreme weather can be traced back to unusually violent volcanic activity, the effects of which were felt throughout much of Europe at the time.

The people of the early Middle Ages, however, did not have the benefit of such scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, they also searched for a valid explanation. The written record shows that the king and his followers were intensely concerned with finding the cause of the hardships, and that they quickly agreed that it must be the wrath of God. In his account of the transfer of the bones of Saints Marcellinus and Peter from Rome to Seligenstadt in 830, the Frankish scholar Einhard explained how the misfortune was caused by the voice of a demon named Wiggo, “for these people defied God's instructions.”

(Württemberg State Library Stuttgart)

Who are we?

Surviving sources, including Einhard’s report, point to the christianitas as those responsible for the weather catastrophes. The term christianitas refers to all Christians, especially the inhabitants of the Frankish Empire. In short, every Christian believer within the kingdom was not only threatened by the wrath of God but was also responsible for improving the situation. After all, according to Einhard, it was "the depravity of the people and the manifold offenses of those ruling over the people" that had led to the existing problems. Thus, the threat and the ensuing explanation thereof created an identity centered on a hierarchical Christian society.

(Württemberg State Library Stuttgart)

What do we need?

The threat was identified quickly for those in power, and loud demands were quickly made about how to deal with the catastrophe. There was unanimous agreement that it was of vital necessity to restore order in the kingdom. Louis the Pious was among the first to truly recognize the threat, and resolving it became his top priority. In an 828 letter to power brokers within the kingdom, he gave clear instructions how to deal with the crisis. He not only discussed the weather extremes that had occurred at the beginning of the decade, but also addressed the problem of Danish invasions in the north, clashes with the Moors in the south, and issues with the Hungarians in the east, all of which had been going on since the mid-820s. According to the king, God was indeed quite unhappy with the kingdom’s people and was testing them time and again. There was thus only one way to finally solve these problems: a godly order needed to be established and respected once and for all!

St. Gallen cloister, early 9th century

What should we do?

The emperor and his court attempted to gain control over the situation shortly after the onset of the extreme weather conditions. Louis acted accordingly and gave penance at the 822 Synod in Attigny. Officially, the act was to reconcile with his brothers who he had exiled, but unofficially he was acting as a role model to his people by proving his duty to God. The timing was important: the kingdom had just suffered under extreme weather conditions in the years prior. Because the emperor was at the top of the kingdom’s hierarchy, there was a belief that his atonement should make a considerable impression on God. Apparently, however, God was not yet pleased because the following years brought heavy rains.

In 825, Louis issued his Admonitio ad omnes regni ordines: a call to order for all the states in the kingdom. In the declaration, he laid down in minute detail his argument that everyone in the kingdom was jointly responsible for its well-being. In 829, the bishops issued a similar call to order in the Frankish Empire with their Relatio episcoporum, and in turn examined the possible causes for invoking the wrath of God.

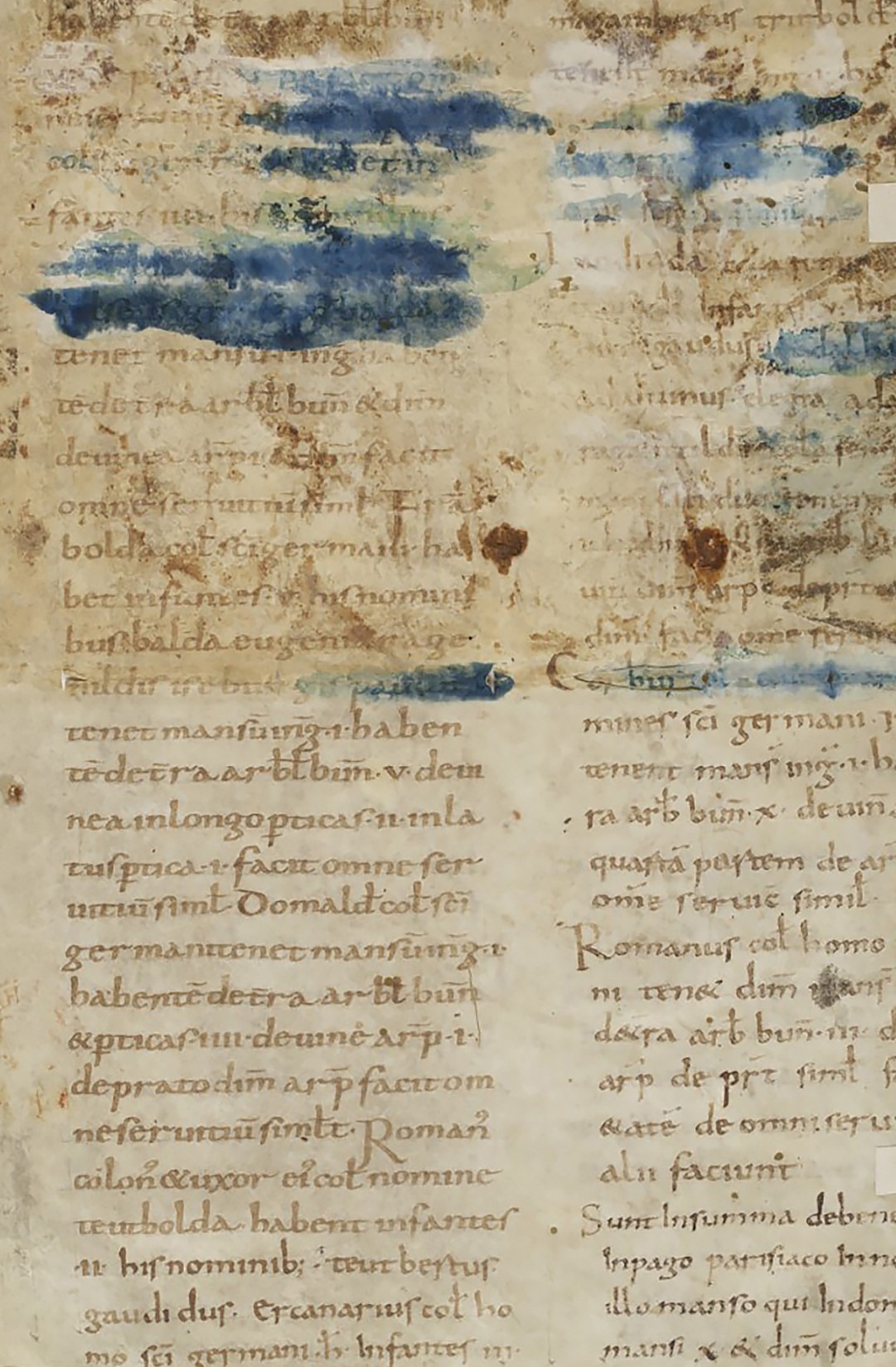

In addition to these decrees, other attempts were made to create order. From an economic point of view, it seemed important to establish order in business enterprises such as the monasteries in order to be better able to deal with poor harvests and hunger. This resulted in Abbot Adalard of Corbie, for instance, implementing a new social order in the monasteries administration in 822. Registries were introduced that served as written records of monastic property and goods; one example is the polyptych of St. Germain-des-Prés in which the abbey recorded the exact size of each peasant settlement, including who lived there and the sum of dues the peasants owed the abbey.

In the years that followed, the call to order remained quite important. Although the threat of weather catastrophes had subsided (with the exception of a few individual events), the empire did not find peace. Louis’ sons rebelled against him twice, and the fratricidal war that only ended with Louis death in 840 repeatedly called the kingdom’s social order into question.

with other case studies.