On January 1, 2020, the Tagesschau reported for the first time on a new and mysterious respiratory disease in China. Less than two weeks later the first case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in Germany. Over the next few months, more and more global regions were affected: Italy, the United States, Brazil. Shortly before Christmas 2020 the virus reached Antarctica. By March 2021, more than 118 million people had been infected with the virus and more than 2.6 million people had died either of Covid-19 or with it. The coronavirus-epidemic had become a pandemic – a global threat.

Perceptions

of Globalisation

One Year into

the Pandemic

Perceptions of Globalisation

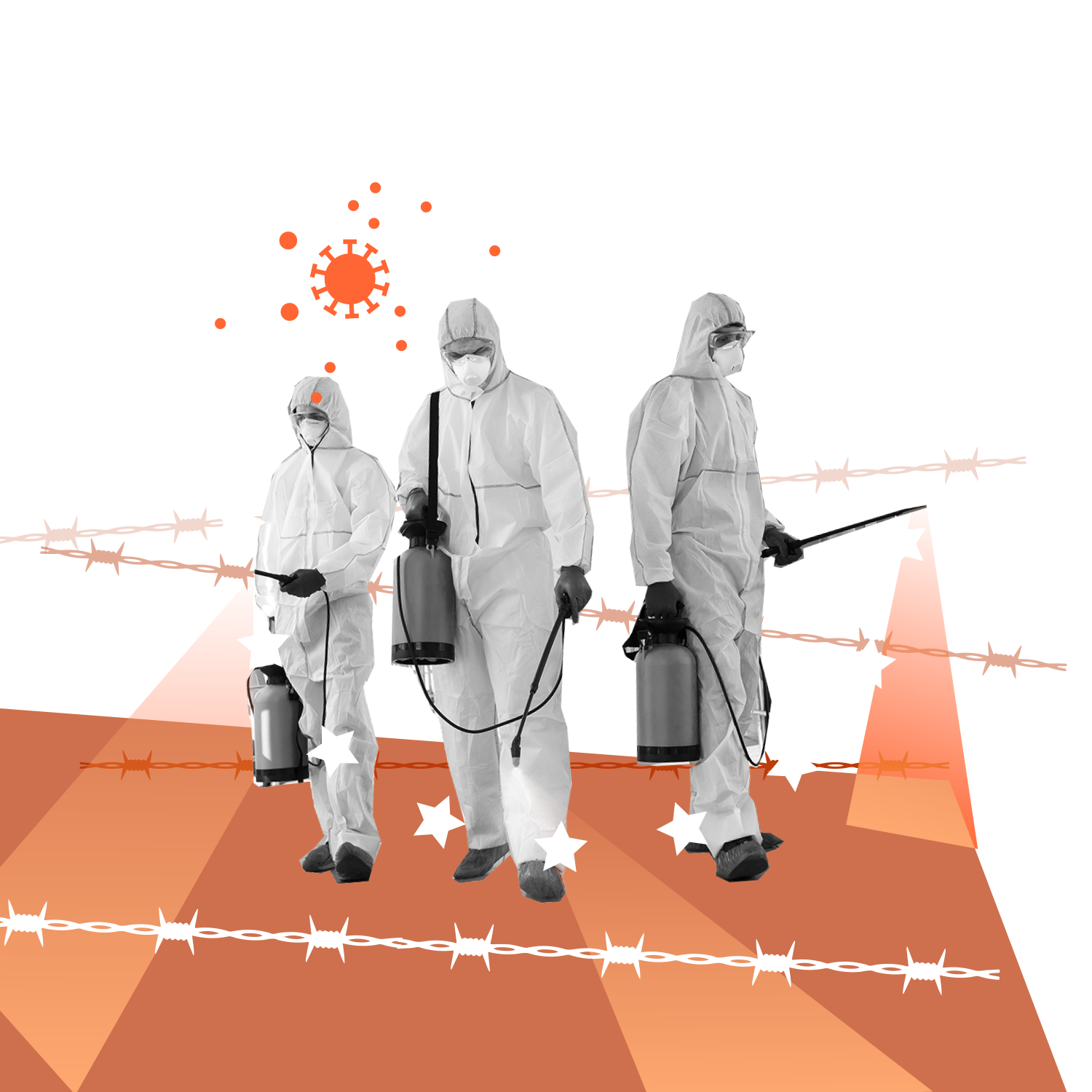

Many governments responded by quickly closing their borders to protect their populations from the rapidly spreading virus. Some held globalisation responsible for the virus’s worldwide spread. The vast global network that we are all a part of even threatened those who typically "win” the most because of it.

The coronavirus pandemic hasn’t only exposed our individual vulnerability, it has also highlighted the fragility of the systems and orders we live in. When put under a magnifying glass, it has shown that globalisation makes people and environments vulnerable in completely different ways. At the same time, globalisation is also seen as a way to fight the virus. As the pandemic expanded, with infection rates rising and falling alongside new scientific discoveries and the development of a vaccine, different patterns of perception and interpretations of globalisation shifted between foreground and background.

What threatens us?

Does globalisation drive the pandemic, or will it become another victim? Some say that in a world where financial activities, trade, and travel are ever more interdependent and interrelated, it is too easy for a virus to spread everywhere. For them, the pandemic should be seen as a chance to stop and rethink this interconnectedness. Others consider globalisation itself as threatened by closed borders and travel restrictions and warn of de-globalisation. Some loud voices have even announced the end of the global network.

The debate changed as the summer approached, after the first wave and the lockdown of spring 2020. When the pandemic shifted and the threat became less severe in Germany, questions arose of what had actually happened. Discussions focused on inadequate crisis management and the slow start of the vaccination campaign. Nobody was talking anymore about the end of globalisation. Instead, the discussion focused on how global interdependence and local and national actions should be intertwined.

Who are we?

Before the coronavirus pandemic, a large majority of Germans identified as citizens of the European Union. One third even stated in polls that they felt they were citizens of the world. This self-image clearly implied that Germany was seen as an established part of a globalised world order. It was also reflected in Germany’s participation in global health initiatives, such as the World Health Organisation.

Fighting the coronavirus pandemic changed this self-perception. During the spring of 2020, “national” issues became more important: border closures, the repatriation of German citizens and a more nationalist rhetoric dominated the debate. With the rapid development of a vaccine, this national focus widened again. Germany and other EU states negotiated together with vaccine producers rather than individually. But it didn’t result in a true global solution in the sense of a global health-plan that German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier had suggested in October 2020.

„And yet we know that these restrictions, this withdrawing behind national borders, are not going to be the solution in our difficult situation. On the contrary, the real path out of the pandemic, the light at the end of the tunnel of our dwindling patience, is to be found in the unprecedented international effort uniting all of you and many more people around the globe. (…) COVID-19 challenges all of us. The virus knows no borders and has no interest in the nationality of its victims. Also in the future, it will overcome all barriers if we do not work together to counter it. In the face of the virus, we are without a doubt a global community. But the key question is: are we able to act like one?

Videogrußwort zur Eröffnung des World Health

Summit 2020, Berlin, 25. Oktober 2020.

What do we need?

Very soon after the outbreak of the pandemic, governments all over the world mobilised enormous financial resources to develop a vaccine. In record time, the international scientific community managed to develop several efficient candidates.

But how were those vaccines to be distributed globally? Was a “world community” possible in such a crisis? In April 2020, the WHO started the COVAX initiative, which aimed to ensure a fair share of necessary vaccines for all countries. In October that year, Federal President Steinmeier appealed to the world, stating that it was vital to act as a community. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres also declared vaccines to be “global public goods”. The public debate was also marked by warnings not to “go it alone”. The President of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, criticised a growing “vaccine nationalism”. There were also discussions of suspending patents on the vaccines to ensure that less developed countries were able to have access to them.

It was a clear message: we won’t be safe until everyone is safe. But when the first doses began to be distributed at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, the tone changed.

What should we do?

By January 2021, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus painted a dark picture. The world was on the brink of a “catastrophic moral failure” because of the huge gap in vaccine distribution between rich and poor countries. In Germany, despite attempts to strengthen the COVAX-initiative, the international dimension of the vaccine distribution plan also moved to the background. The public debate focused mainly on how the entirety of the German population could be vaccinated as quickly as possible. There was little or no thought given to supplying vaccinations to high-risk groups worldwide. While rich countries secured a large percentage of the available vaccines, more than 85 low-income countries had to accept that their vaccination programs would probably only start in 2023. This discrepancy between global rhetoric and national actions clearly illustrated a different perception of globalisation. Is the “global” part of that term truly more than the sum of the national interests of dominant states?

with other case studies.