The 7th century was a time of upheaval. In the west, the Goths, Franks, and Lombards were building a new, medieval world upon the ruins of the Western Roman Empire, while in the east, the remnant of the once mighty empire was fighting for its very survival. The constant war against the Persians had irreparably eroded the eastern parts of the kingdom. Powerlessly, the Romans witnessed the fall of Jerusalem in 614 and Alexandria in 619. The empire was also under siege from the northern Avar and Slavic tribes who invaded via the Danube, plundering and vandalizing as they moved closer and closer to the capital until they ultimately stood in front of the city gates of Constantinople in 626.

The Siege of

Constantinople

626

A City

Under Siege

Avars, Slavs

and Persians

at the gates

In the capital, the situation seemed hopeless. While the Avars were approaching the city walls armed with heavy siege engines, the Persians set up camp on the Asian side of the Bosporus, a position that threatened imminent attack. To make matters worse, the citizens of Constantinople were left on their own. Emperor Heraclius was campaigning in the east, so no help from his end was in sight. But the city did not think of surrendering. With the hope of divine assistance and united forces, they took on the immense task of defending the city walls against the Avar attack while also attempting to prevent an imminent Slavic invasion by sea.

What threatens us?

Since Justinian’s rule (527–565), the Roman Empire’s political situation had deteriorated rapidly. The Persians, the empire’s archenemies, had completely overwhelmed the eastern regions with constant war. Earlier peace talks had failed, and in the summer of 626, a Persian force stood armed and ready just across the Bosporus. The only thing separating this army from Constantinople was a narrow strait. While facing this imminent attack across the strait, the city also faced the threat of Avar and Slavic invasions from both land and sea. The invaders pillaged the surrounding towns and villages, effectively cutting the capital off from supplies, and began setting up heavy war equipment in the process. Their leader, the Chagan, was a shrewd man who had nearly captured the emperor a few years earlier. The threat was even more dire this time because the emperor had left the capital on a campaign against the Persians two years earlier and was much too far away to intervene in time. Instead, the heavy mantle of responsibility lay upon two men, the Patriarch Sergios and the Roman general Bonos, both of whom sought to prevent a mass panic and scrambled to quickly organize the city’s defense.

Who are we?

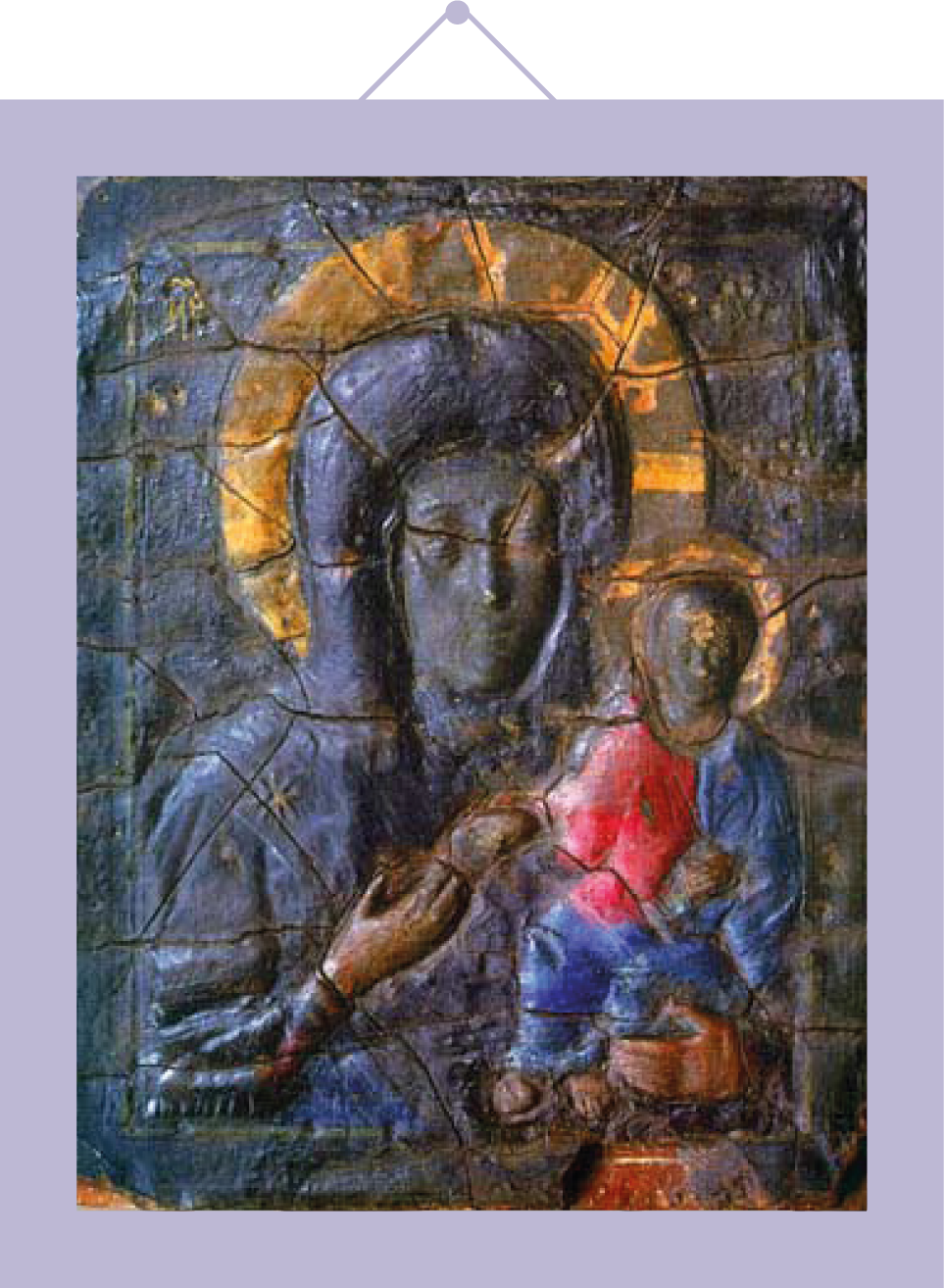

The city walls were the tangible symbol of the border between the known and the unknown, the insider and the outsider, citizen and stranger, friend and foe, and even more poignantly, between the besieged and the assailant. Apart from this stone wall, there was another ideological barrier that separated the citizens of Constantinople from their invaders: the Christian faith. In contrast to the deeply religious population of the empire, the Avars, Slavs and Persians did not believe in the Christian God. In the eyes of the besieged, the unbelievers were not only a threat to the city but to all of Christianity. According to contemporary sources, the Chagan was believed to be a spawn from hell, the Antichrist incarnate. This directly affected the strong sense of community and solidarity for the people in the city. Even ordinary seafarers who were only in Constantinople temporarily felt connected to the inhabitants and supported them to the best of their ability. They did not merely see themselves as defenders of a besieged city, but as righteous citizens fighting for their Christian convictions. Thus, Constantinople became a bastion of Christianity.

What do we need?

Since the departure of Emperor Heraclius, the fortunes of the city and its inhabitants had been under the direct control of Patriarch Sergios and General Bonos. It was uncharted territory for everyone concerned because Constantinople without the emperor had become unimaginable. During the siege, it was thus all the more important to avoid the impression that the emperor had abandoned his people, a feat that was accomplished with the assistance of poets who invoked the support and concern of the emperor in their works. Indeed, the absent ruler had not abandoned his people, and he sent numerous letters in which he gave Bonos instructions and advice. But the citizens also believed there to be more immediate assistance at hand: that of the divine. Sergios repeatedly encouraged the people, prayed with them and stood on the city wall holding a picture of the Virgin Mary in defiance of the enemy at the gates. In the end, the people became so convinced of divine support that they believed to have seen the Virgin Mary on the city walls wielding a sword against the enemy.

What should we do?

The Patriarch’s encouragement provided the necessary will to persevere and solidarity within the population. General Bonos also proved his ability to lead by organizing an effective defense of the city walls and by motivating his men. They fought daily small skirmishes against the Avars and the Slavs in front of the city gates. The decisive turn in the siege, however, was achieved with trickery. With a cunning bluff, Bonos was able to keep the Persians from attacking, which in turn allowed him to thwart the Avar attack. Bonos learned that the Slavs planned to attack the city from water upon receiving a fire signal, which would distract the defenders of the city so that the Avars could storm the walls unhindered. Instead, Bonos cleverly gave the supposed attack signal himself, which led the Slavs to attack, where they were surprised and crushed by the waiting defense forces. The blind-sided Avars could only helplessly watch the bloodbath of their allies and were forced to break off their siege. They would to never fully recover from the decisive defeat. The citizens of Constantinople, on the other hand, were the triumphant victors, and subsequent sieges by Arabs, Bulgarians, and Magyars seen as harmless in comparison. It was not until the 13th century that crusaders were able to conquer the city. But by then, the Constantinople of the seventh century had long since disappeared.

with other case studies.