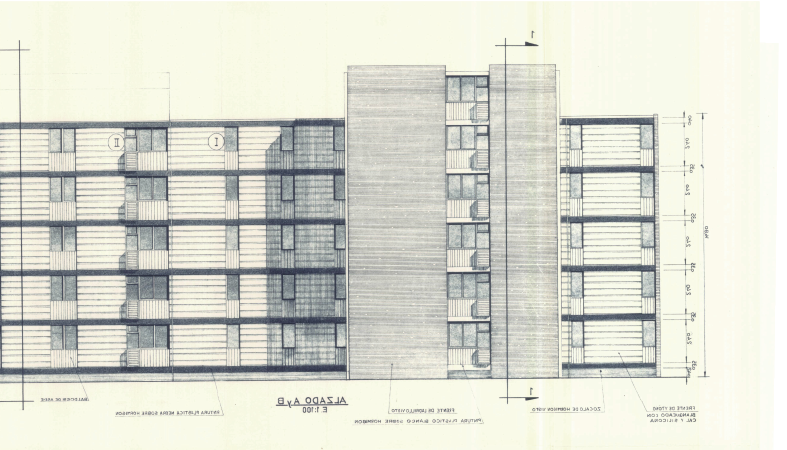

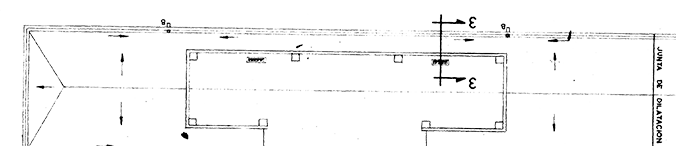

Villarriba is a poor, ethnically diverse neighborhood in the Spanish city of Murcia that, over the last two decades, has had to struggle with massive deterioration of infrastructure and with increasing social divisions. Originally built as a social housing project in the mid-1960s during the Franco regime to provide affordable housing for low-income families, a large portion of its current population are part of the Spanish Roma ethnic minority, which is why the area is often described as the “Gypsy Quarter”. Starting in the mid-1990s, immigrants from countries such as Morocco, Ecuador, Bolivia, Ukraine, and Senegal have moved into the neighborhood.

A Failed

Housing Project

in Murcia

A Neighborhood with an Uncertain

Future

A divided

neighborhood

Through the decades, the neighborhood experienced increasing impoverishment and public neglect. Buildings decayed, social services were reduced, and poverty and social problems have visibly increased. The political mobilization of a neighborhood association and church activists against this process turned out to be unsuccessful. In the mid-2000s, a property developer proposed a privately financed rehabilitation project. He planned to tear down and rebuild the entire neighborhood and promised to provide the current residents with larger and more modern apartments. The project never came to fruition, but the conflicts that erupted as a result of the plan divided the neighborhood even further.

What threatens us?

The progressive deterioration of Villarriba’s buildings became the visible symptom of an worsening socio-economic situation from which the state withdrew further and further. As the process continued, the neighborhood and its inhabitants experienced increasing social stigmatization. Caught in a vicious cycle of impoverishment and deterioration, they were marginalized by residents in neighboring areas, and were increasingly seen as a threat. Thus, while the residents of Villarriba experienced the decline of their own neighborhood as a threat, they themselves came to be seen as threats by others.

Furthermore, the potential rehabilitation that might have offered a solution to both threats, became, indeed, a source of threat for the cohesion of the neighborhood: due to the internal divisions over the rehabilitation project, two oppositional groups view each other and their respective model of rehabilitation as threatening.

Who are we?

Villarriba’s inhabitants were — and still are — a diverse group of people. The long-established population was proud of its working-class identity and had a pronounced sense of community and solidarity, reflected in a dynamic group of activists. Admittedly, many of these activists left Villarriba when they founded families or were able to climb the social ladder. Still, they felt a moral responsibility to help the neighborhood. This communitarian sense of belonging broken down, however, in the context of the rehabilitation project. The “old activists” were accused of no longer representing the interests of the neighborhood. As a result, the neighborhood split into two coalitions: One supported the private redevelopment program, while the other fought against it and asserted that the renewal of the neighborhood was the responsibility of the state. As a result of these developments, today the identity of the neighborhood appears internally fragmented and externally stigmatized.

Church reforms in

the Carinthian Alps

Division and cohesion

in threatened social orders

In threat situations, people become conscious of certain aspects of the society in which they live that they had never or only rarely thought about before. This can change the stories that people tell each other about themselves and others, and thus the characteristics that they attribute to one another. In turn, the borders that define membership in a group can shift. In Villariba, a proposed rehabilitation project in an area characterized by stigmatization and economic decline led to division in the local social order, and led the people of the area to become alienated from one another.

But that does not always have to be the case. Other groups have reacted to threats by closing ranks, helping each other, and by stubbornly confronting adversity. The residents of the Austrian village of Kappel, for instance, could never have imagined that the emperor would one day try to ban their religious rituals and practices. But that is exactly what Joseph II tried to do in the 1780s, directly threatening the everyday lives and the spiritual salvation of the devout residents. Unified by their faith, rituals, and proud local identity, the Kappelers refused to give in, true to the adage: anyone who doesn’t belong to us belongs to them. Representatives from the government were given a choice: either they spoke with everyone, or with no one.

What do we need?

While there was a broad consensus among the different neighborhood organizations of Villarriba on the need to overcome their collective marginalization, the two groups disagreed about how to reach their goal. The aims and strategies to gather support of each group were so different that two parallel worlds emerged.

Members of the first group gathered around the “old activists” and fought against the private developer’s project. Instead, they called for an international contest of ideas and saw the city government as responsible for leading the redevelopment of the neighborhood. People in the second group, on the other hand, supported the private redevelopment project. They rejected the legitimacy of the “old activists” to speak for the neighborhood and boycotted the proposals of the first group.

What should we do?

Although the private redevelopment project was sanctioned by the municipal government in the mid-2000s, the project was never realized. The property developer blamed the global financial crisis and claimed that it would have to wait for better economic conditions to be able to finance the project. After being pressured by the first group, at the end of 2016, city administrators ultimately approved a new project to improve the social situation and urban deterioration of Villarriba. However, the first group criticized the move as nothing but a declaration of intent without any practical consequences. For the second group, the city’s new plans would not go far enough to really solve the neighborhood’s problems, and claim the need to stick with the property developer’s project.

Today, the situation in Villarriba is worse than ever. None of the promises made by any of the actors were ever realized. Among the residents there is a deep mistrust in the abilities of both municipal institutions and the developer, and hope for an improvement of the situation is fading. Now, the ever-worsening infrastructural situation is accompanied by the deep division among the residents regarding the failed redevelopment project. Overcoming this gap represents yet another challenge for both sides, particularly because support from the city is heavily dependent on the neighborhood’s agreement. Attempts have recently been made to solve the conflict by focusing on the question of social justice instead of continuing to fight about the property developer’s project, but the future of Villarriba remains uncertain.

with other case studies.