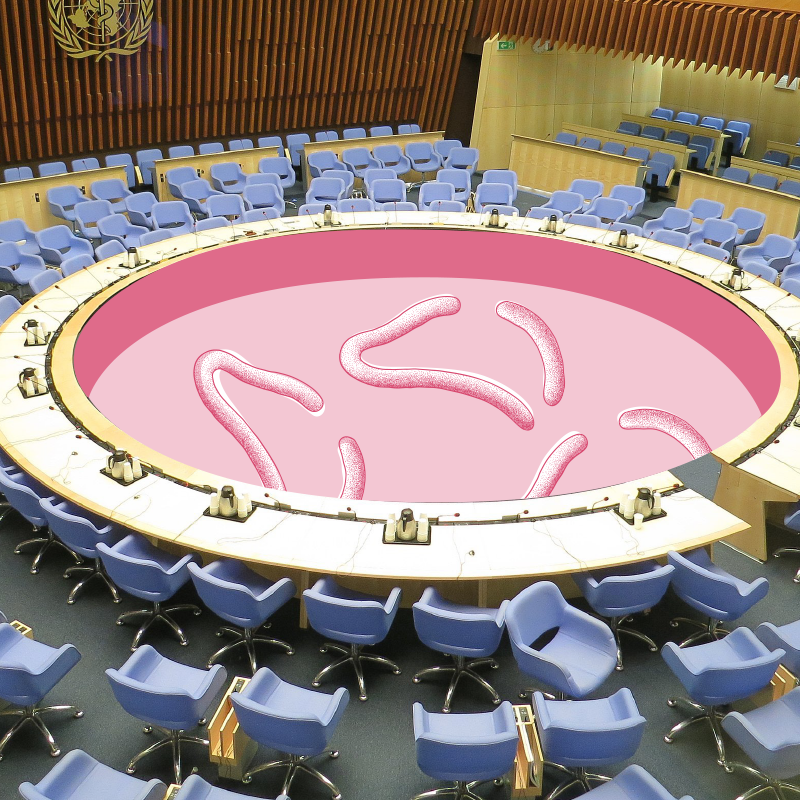

In the summer of 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of Ebola in parts of West Africa to be “a health emergency of international dimensions”. Before that, local governments had announced a state of disaster. For the first time since its discovery in 1976, Ebola had reached densely populated areas connected to international travel. Fear of a pandemic was spreading – a scenario that so far had been unthinkable. Among experts, Ebola was not considered a threat to the world population because previous outbreaks had remained local. Until the infection figures declined in June 2016, the deadliest form of the virus had spread across West Africa.

Ebola in

Western Africa

The deadliest pandemic?

Limitations of Medicine?

After the Ebola outbreak, the term “distrust” could be found more and more frequently in newspaper articles and medical journals in reference to modern medicine. Medicine, said the international critical voices, was marked by large gaps in knowledge, even in the 21st century. Current medical knowledge could not be available everywhere and for everyone. Medical practitioners, too, began to question the capacity and practices of their science as well as the efficacy of established health systems. The organization Medicine sans Frontiers declared: “The Ebola epidemic proved to be an exceptional event that exposed the reality of how inefficient and slow health and aid systems are to respond to emergencies.”

What threatens us?

Experts were undecided for months on end about the extent of the imminent threat. In March 2014, a special laboratory in Lyon found that the rapidly spreading infections in West Africa were caused by the deadliest variant of the disease. An infection with “Ebola type Zaire” proved fatal in 70%–90% of all cases. But despite the loud warnings from Medicine sans Frontiers, the WHO responded cautiously even in April. They reported news about the outbreak but did not take any action. A WHO spokesman, Gregory Hartl, dismissed the MSF report and the organization’s demands as alarmist.

Don‘t exaggerate. Ebola can kill up to 90% of those infected and in this particular outbreak fatality rate is less than 67%.Gregory Hartl, Senior Communications Advisor of the WHO, responds to reports of the organization Medicine sans Frontiers in April 2014

Who are we?

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa surprised the WHO and stretched health systems and aid organizations to their limits – even though one might have expected them to be better prepared for the outbreak of a deadly virus. After all, the expression “new or emerging infectious diseases” had been an established term among medics since the 1980s, triggered by the new immune deficiency illness AIDS. It still reflects the perception that even after a phase of significant successes in the battle against infectious diseases, humankind (and medicine) has limited power when confronted by epidemics.

What do we need?

As with all infectious diseases, it was necessary to take steps to prevent the spread of the virus as quickly as possible. But under massive pressure, it proved impossible to impose some of the “correct” actions against infectious diseases, such as the establishment of quarantine, which failed in local circumstances. At the same time, proponents of traditional medicine demanded that western methods should also integrate alternative knowledge. Locally, some complained about the lack of contact with non-medical disciplines such as ethnology and anthropology or with local healers. They had a role to play as intermediaries between the suspicious West African population and foreign helpers and would have been able to build trust in the activities of medical personnel. Governments and international aid organizations tried to clarify knowledge and highlight the danger of Ebola. Still, not much was known in the population about the infectious disease despite earlier and mostly locally limited outbreaks.

An Ebola-team from the WHO, UNICEF and other organizations in September 2014 uses vehicles with loudspeakers to inform the partly skeptical population of Monrovia (Liberia) about the threat of Ebola (copyright AllAfrica.com)

What should we do?

Threatening messages, such as “Ebola kills”, had initially greatly unsettled the afflicted societies, so the WHO worked on concepts to address specific groups. While remaining focused on Ebola, campaigns demonstrated how general hygienic measures could help people protect themselves. The campaigns were successful in part but could not prevent the disease from spreading for nearly three years. On June 9th, 2016, the health authorities did not register any new cases and the WHO declared the outbreak over. Official figures showed that by that point, 28,646 people had been infected, of whom 11,323 had died.

What followed was an intense discussion among experts about reforming global measures for the prevention of infectious diseases. It would contain a close network of early warnings and an increase in regional WHO offices. Non-government organizations (NGOs) such as Medicine sans Frontiers were to receive more support. Today, concepts are being developed to separate basic medical support and disaster protection from developmental aid. Such efforts are based on a vision of mutually assisting supply systems encompassing all nations.

with other case studies.