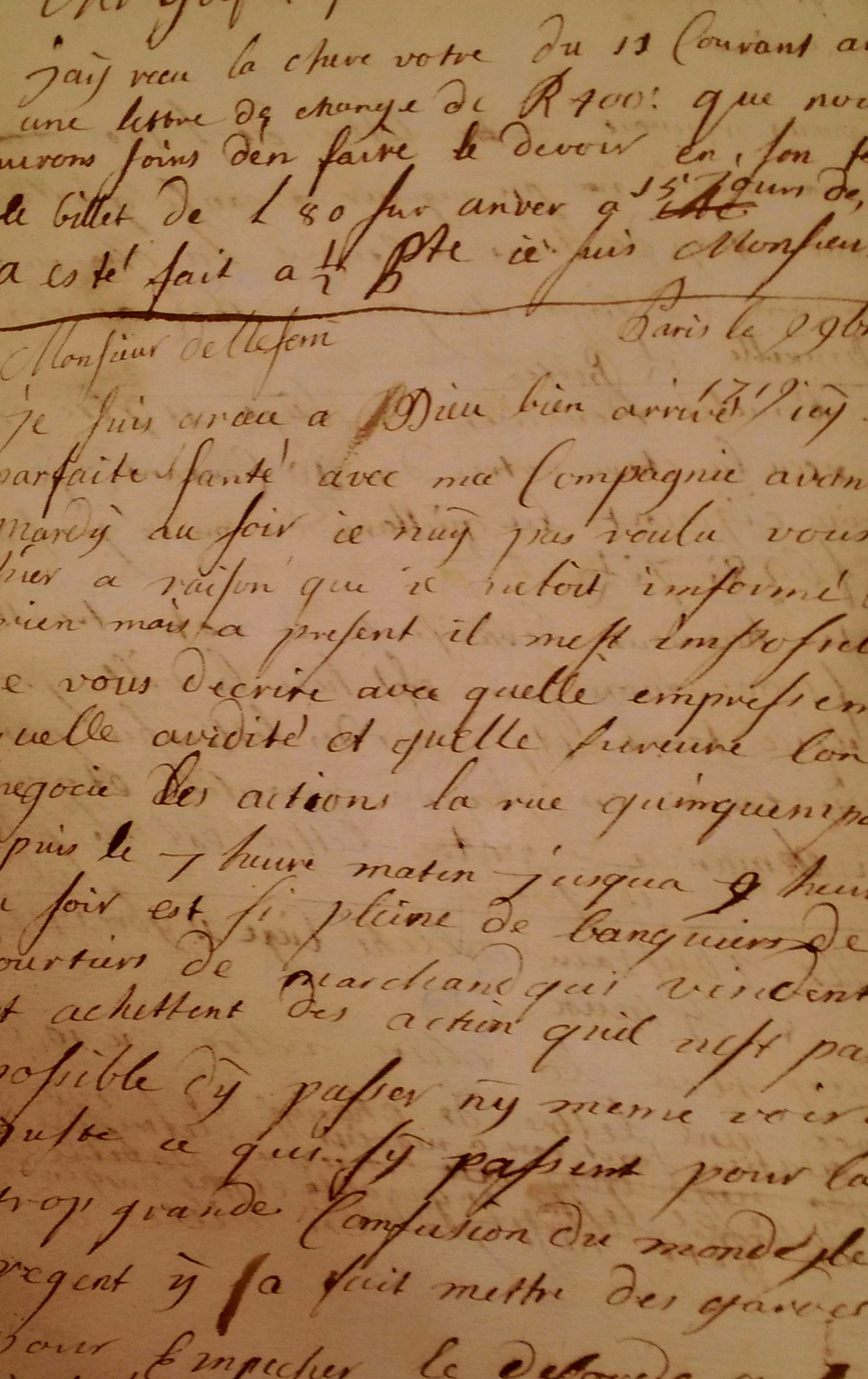

In 1720, Paris and London were the scenes of the first stock market crashes, which would go down in history as the Mississippi Bubble and the South Sea Bubble, respectively. The holders of government bonds were lured to exchange them for shares in large companies. From the government's point of view, this had several key advantages: the international trading companies were able to expand their activities, the economy was stimulated, and public debt was significantly reduced. Market manipulation and the introduction of new, risky possibilities for speculation such as options and futures, however, succeeded in creating a euphoria that drove share prices up to twenty times their nominal value.

"Futures" are contracts for share purchases. The price is fixed at the time of acquisition, but the actual purchase is carried out at a later date. Thus, the buyer speculates that the price of the stock will rise until then and that he will then be able to resell at a higher price than the purchase price. In the case of "options," an investor puts a down payment on a share, giving him the right or option of deciding at a future date, whether he wishes to buy the share. If he decides not to, the deposit is lost.