The Reformation started the modern era with a bang: Martin Luther and other pioneers of the new faith shook the very foundations of a society that was thoroughly shaped by religion. The new interpretation of faith also affected the Catholic monasteries, especially women's convents, because the Reformation vehemently rejected the ideals of an isolated lifestyle shut off from the outside world. Instead, the new faith called for a woman’s rightful place to be part of the family. The advocates of Reformation therefore sought to disband monasteries. For the nuns, this meant abandoning a centuries old way of life, and leaving behind their identity as religious women.

The dissolution of

monasteries during

the Reformation

A way

of life

challenged.

The Dominican sisters

in Weiler

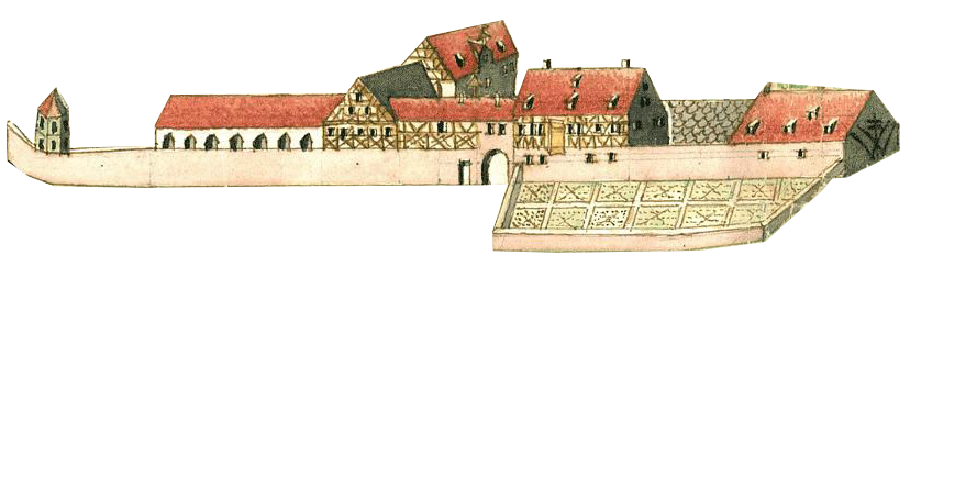

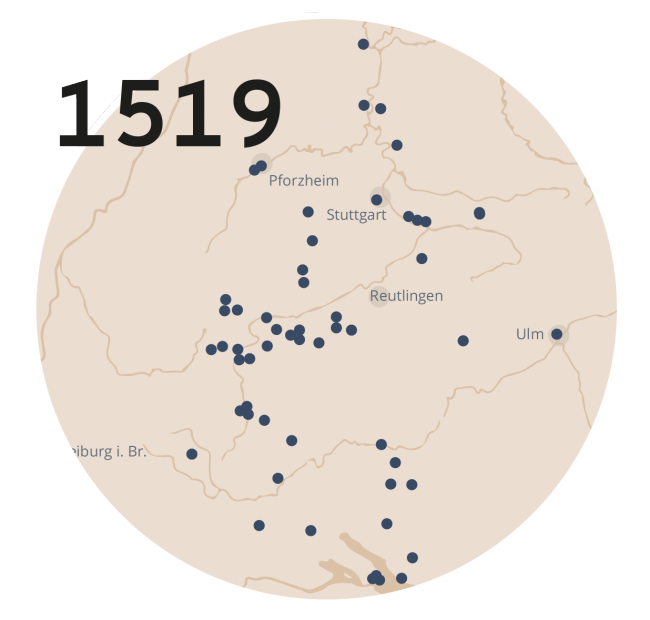

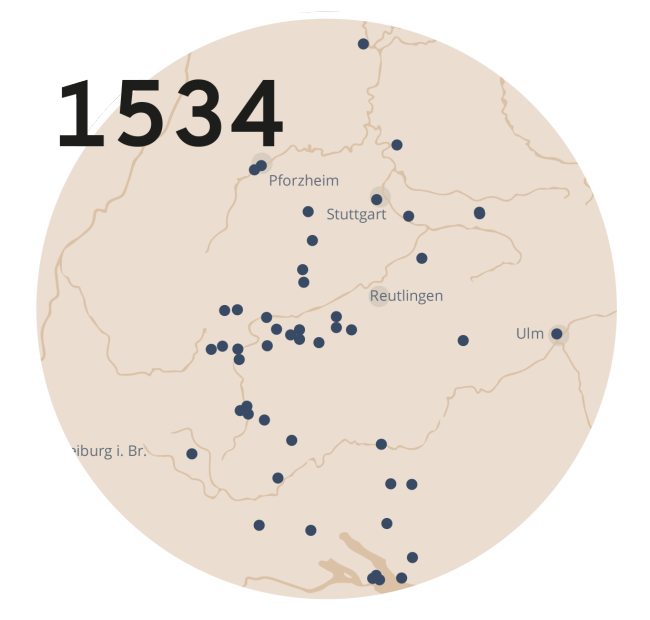

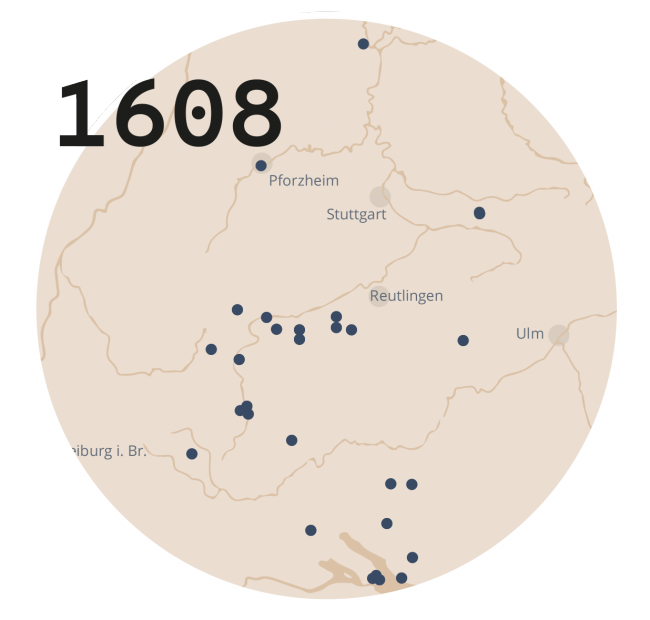

The nuns of the Dominican Order, who had a large population in southern Germany, were put under extreme pressure and existential distress by Duke Ulrich, who had adopted the new faith in Wuerttemberg and began enforcing it after 1534. In addition to religious motives, economic and political interests also played a role for the Wuerttemberg sovereign: the monasteries usually owned quite a bit of land and property.

To enforce the new faith, nuns were forbidden from taking on new sisters, and the administration of the convent was taken out of their hands. Masses were also effectually banned because Protestant pastors were brought in to replace the Catholic priests. These dramatic changes were meant to force the nuns to adopt the new faith and to leave the convents. What did the Reformation mean for the individual nuns? To answer this, we take a closer look at the Dominican Sisters in Weiler, a convent nearby Esslingen.

What threatens us?

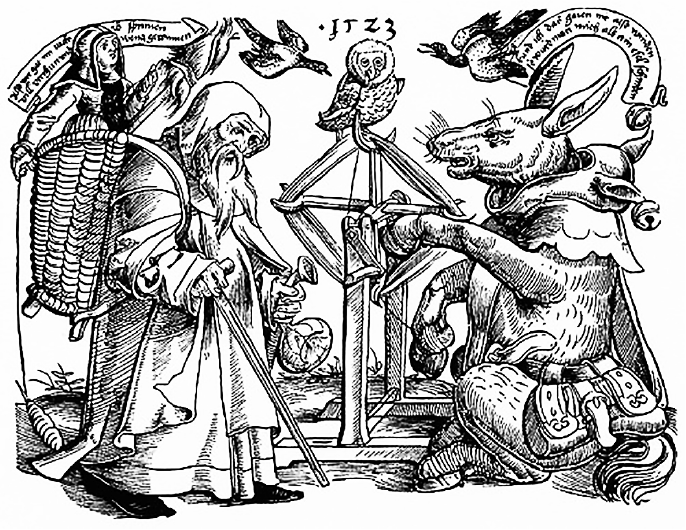

Criticism of the monastic way of life was nothing new in the 16th century. Time and again, nuns and monks were accused of not following the rules of their own order. But the Reformation took it a step further by fundamentally questioning the entire monastic way of life.

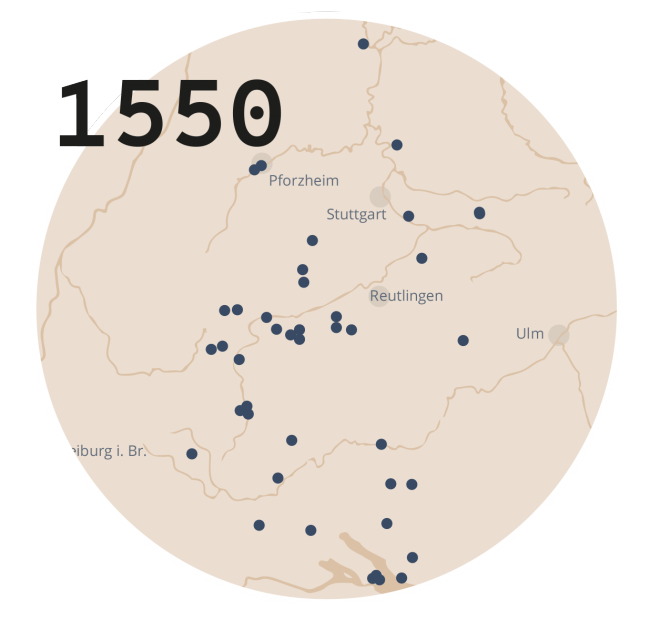

In September 1552, the Weiler nuns requested to be left alone to their ‘old Christian ceremonies’ and their ‘honorable, godly way of life’. This response clearly shows that they felt their very way of life to be under attack. The very essence of what shaped their daily life was to be abolished: the liturgy of the hours, the Latin choral singing, the confession, the holy communion; in other words, every aspect of Catholic life and their very existence as nuns. The threat became very real in Weiler when envoys of the Duke of Wuerttemberg attempted to enforce the Reformation repeatedly with various strict measures from the mid-16th century onwards. They attempted to convince the nuns of the new faith through spiritual instruction by Protestant preachers and individual interviews.

Who are we?

In 1560, the Weiler convent was made up of about a dozen nuns. Because of their monastic way of life, shut off from the outside world, it is reasonable to assume that ‘we’ meant for these few nuns the convent. Barbara Morlockin von Hohenwart, for example, made it quite clear that she did not want to be separated from the convent as it symbolized her main source of identity. Even though statements that clearly define the convent as a reference point, and fixes the nuns’ identity to that point, are very rare in contemporary sources. Yet, the Reformation’s threat to their spiritual way of life did force the nuns to clearly articulate why they wanted to stay in the monastery. These statements show that the identity of the nuns did not only referred to the convent; the “we” conceived of by individual nuns was multi-facetted. The prioress’ sister, Agnes Ehingerin, for instance, invoked the loyalty of her entire order, the Dominicans. A sense of community was also created by the Weiler nuns through their self-description, which denoted them as ‘poor, stupid women folk,’ helpless women who were facing the threat of the Reformation head on.

What do we need?

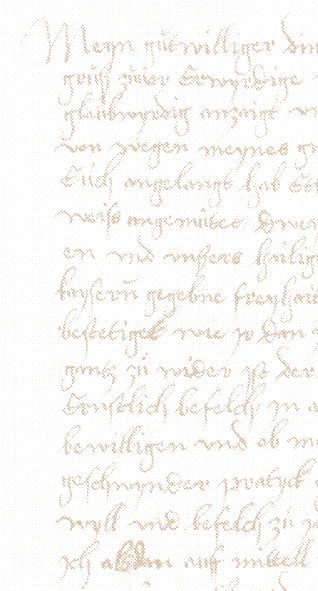

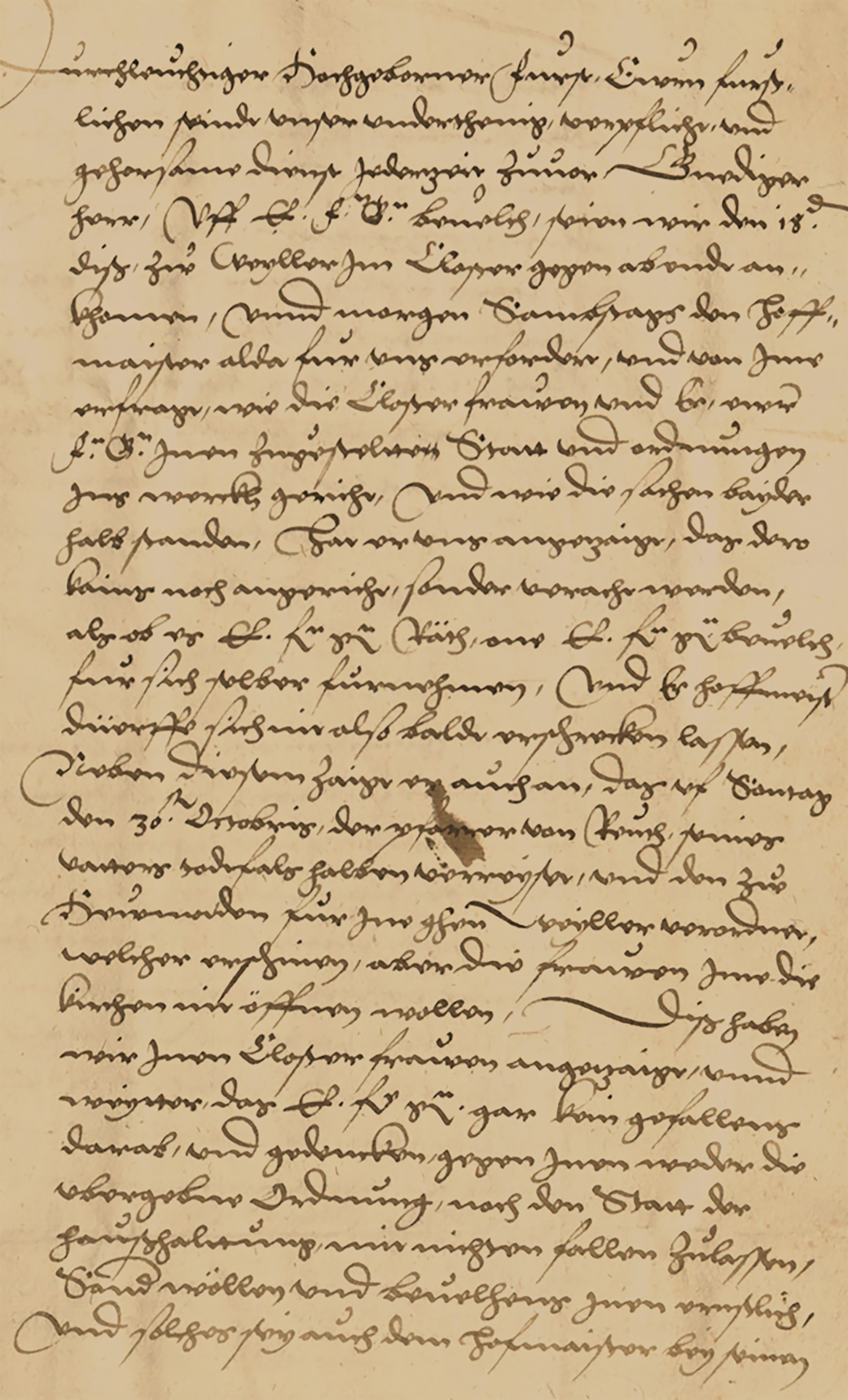

The Weiler nuns lived sealed off. According to the vows they took upon becoming a nun, they were not allowed to leave the confines of their monastery. But, in such threatening times they were forced seek contact with the outside world. Thus, the exchange of letters with families and friends was of particular importance at this time. Although no letters from the Weiler nuns to their confidants have survived, a 1553 reply letter addressed to the prioress has. The letter was sent by the Dominican provincial superior John Pesselius, a senior member of the order. He was considered to be ‘one of us’ by the Weiler nuns with regard to the Reformation threat. Pesselius was informed about the difficult situation the nuns found themselves in. In his letter, which reads like an instruction manual, he informed the prioress Ursula Ehingering of the convent’s centuries old legal status and provided manuscripts that documented its history. The main point was that under no circumstances should the nuns bow to the demands of the protestant Wuerttemberg sovereign. At the same time, said the Dominican, he would throw his hefty political weight in the balance so that the convent would not be ‘pushed into undue and improper things.’

What should we do?

To cope with the threat, the nuns followed the provincial superior’s instructions. By 1556, when the convent had not had a Catholic priest to guide them for many years, and as the situation became increasingly difficult, they informed the duke's Reformation commissioners of their long-standing rights that had been granted to them by the emperor. This bought them time from the sovereign’s grasp. At the same time, the prioress – likely out of fear they would be confiscated – secretly moved valuable silverware and other monastic objects outside of the duchy. Although they were obliged to follow their sovereign’s will, the Weiler nuns were thus able to forestall the changes of the Reformation and maintain most of their way of life for many years using such delaying tactics. Indeed, the Weiler convent was not finally dissolved until the last nun, Barbara Morlockin, died in 1592.

The Siege of

Constantinople

626

What remains

after the threat?

It is rare for a threat to be warded off entirely, but it is also not normal for the social order to dissolve completely. In the case of the convent in Weiler, however, we are confronted by precisely just such an example: the convent was ultimately disbanded. In a different case, namely the siege of Constantinople, the residents of the city were able to successfully repel the threat of the besiegers. But both cases exhibit strong solidarity between individuals in the social order. The local communities in each were protected by walls and could close themselves off to their threatening environments. But only the residents of Constantinople were successful in mobilizing the necessary means to repel the threat, while the community of nuns in Weiler ceased to exist.

Even in Constantinople, however, although everything appeared to return to normal after the siege, the threat left its mark. The people began to consider what had helped them avert the threat – and what had not helped them. The residents of Constantinople hadn’t needed their Emperor to defend their city, an experience that remained in people’s memories.

with other case studies.