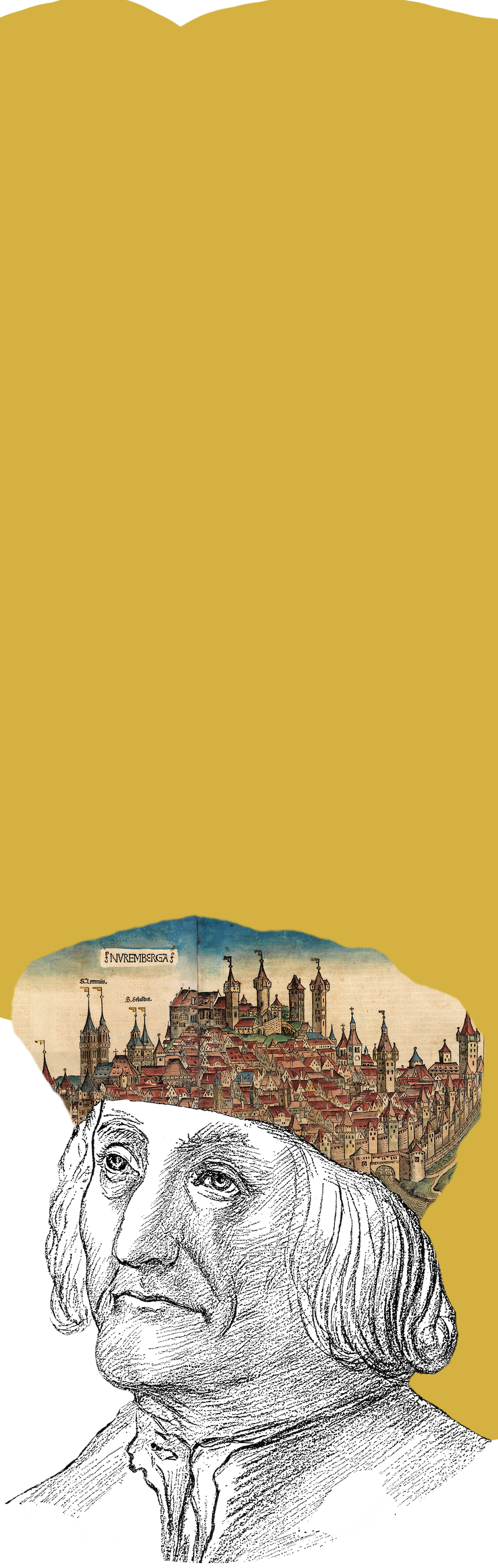

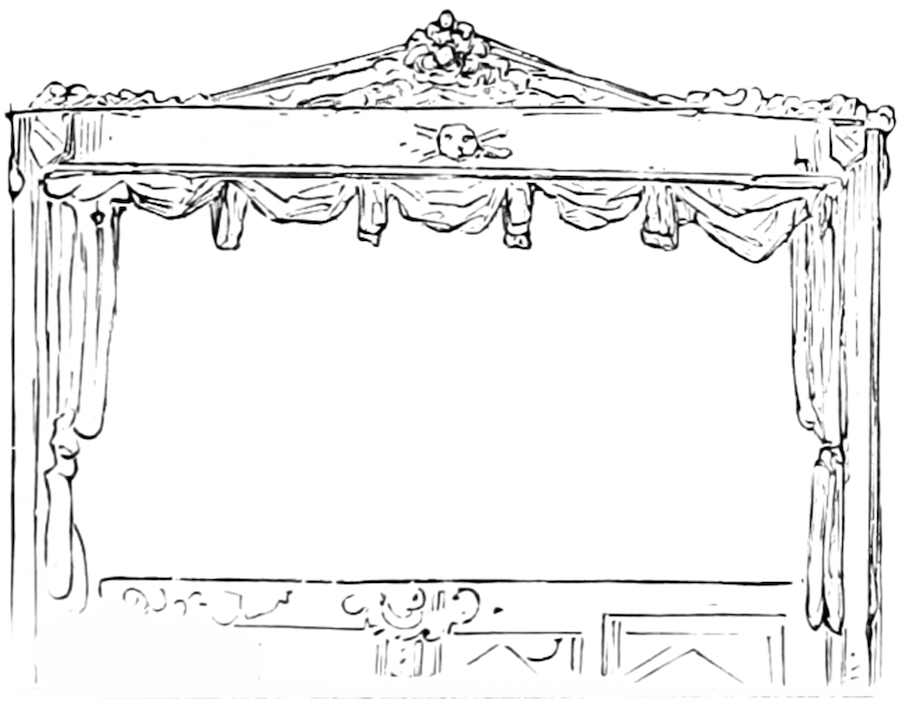

Going to the theater was very popular during the late Middle Ages. Crowds flocked to cities to see the plays, many of which often lasted several days. In the era before radio, television and internet, the theater was the mass media of its time, and was able to reach (and thereby influence) people from all social classes. A case from the city of Nuremberg clearly illustrates how theater was used to convince the audience of a threat that was actually completely baseless, but which nevertheless had serious consequences.

Anti-Jewish

theater in

the late Middle Ages

A threat

on stage

An influential performance

in Nuremberg

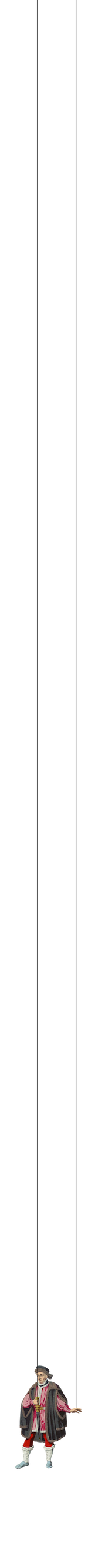

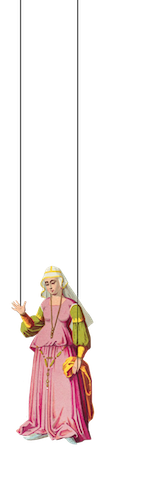

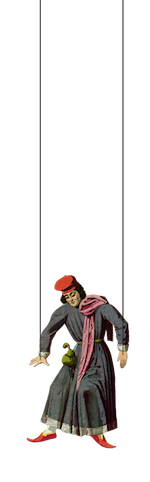

At the end of the 15th century, the Nuremberg city council had been trying for years to evict the local Jews and to appropriate their property. But to do so, the council needed the permission from the king, which he initially refused to give. Around this time, a series of anti-Jewish plays by the Nuremberg surgeon and writer Hans Folz were publicly performed with the full approval of the city council. The plays depicted Jews as the enemies of Christians and portrayed them as a clear threat to all of Nuremberg’s citizens. Here, we focus our attention on the most drastic piece, written and performed between 1486 and 1494: Der Juden Messias (The Jewish Messiah).

What threatens us?

The Juden Messias begins with the arrival of the Duke of Burgundy in Nuremberg at carnival time. The nobleman meets the prophetess Sibylla, who tells him of a Jewish conspiracy which claims that their messiah had come and would soon lead them to world domination. During the play, the prophetess exposes the Jewish Messiah as a fraud and as the Antichrist. She wrings a confession of Jewish machinations out of him that confirms all of the anti-Jewish fables of the time. For example, the false messiah "confesses" that the Jews would abduct Christian children and murder them in their rituals. This confession was deemed credible because it came directly from the mouth of a Jewish character. In this way, the play solidified anti-Semitic prejudices among its audience and made Jews appear to be a real threat.

Who are we?

The play directly depicts the Jewish population of the city as a threat to the citizens of Nuremberg. The play’s plot takes place in Nuremberg at carnival time – the same time that the actual play was also performed – which makes the Jewish threat seem to be a current threat. The audience could easily equate the Jews depicted on stage with the Jews living in the city and could thus truly feel the threat, which actually made it real. At the same time, the play created a strong sense of unity by giving the citizens a common enemy. The public was intended to become aware of a common identity, not just as citizens of the city of Nuremberg, but above all as Christians.

What do we need?

The performance of the play came at a time when the city council was striving to gain royal approval for the expulsion of the Jews. In the play, the arrival of the duke with his military strength is the necessary condition for the conviction and expulsion of the Jews. The prophetess Sibylla reveals the conspiracy to the duke and the Jews are punished with the help of his soldiers. The play could thus be used as a political tool to create an anti-Semitic climate in the city and at the same time to put political pressure on the authorities to follow the play’s recommendations for action. This clearly illustrates how the stage could effectively be used for political purposes and to influence the populace at a time well before the concept of mass media came into play.

What should we do?

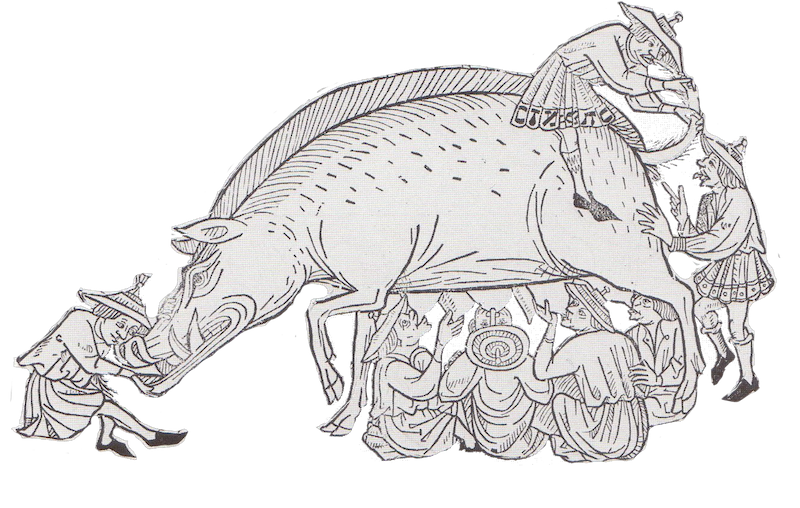

A sow is brought in and the Jews are instructed by the herald of the Duke of Burgundy to lie down under them. The Messiah has to lie down under the tail.

The measures enforced in Der Juden Messias to deal with the Jewish threat are drastic. Following the false messiah’s confession, he and the Jews are punished, dispossessed, and expelled from the city. The punishment is especially humiliating. The Jews and their messiah are forced to reenact a well-known caricature: the Judensau, which means they are forced to lie under a sow, suckle on her teats and eat her excrement. This depiction was common in the late Middle Ages and was often found on stone reliefs on many churches – such as on the St. Sebaldus Church in Nuremberg. The image is particularly humiliating, because the pig is considered to be unclean in the Jewish tradition, and according to Christian tradition it is a symbol of the devil. The play Der Juden Messias aims to defame the Jews as threatening and create support for their expulsion from the population. In the years that followed, this became a bitter reality; the city council ultimately received royal permission to dispossess the Jews and expel them from the city. The last Jews left Nuremberg in 1499.

with other case studies.