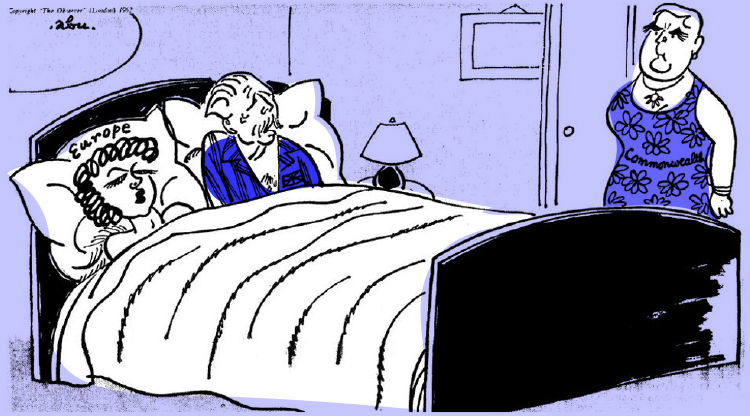

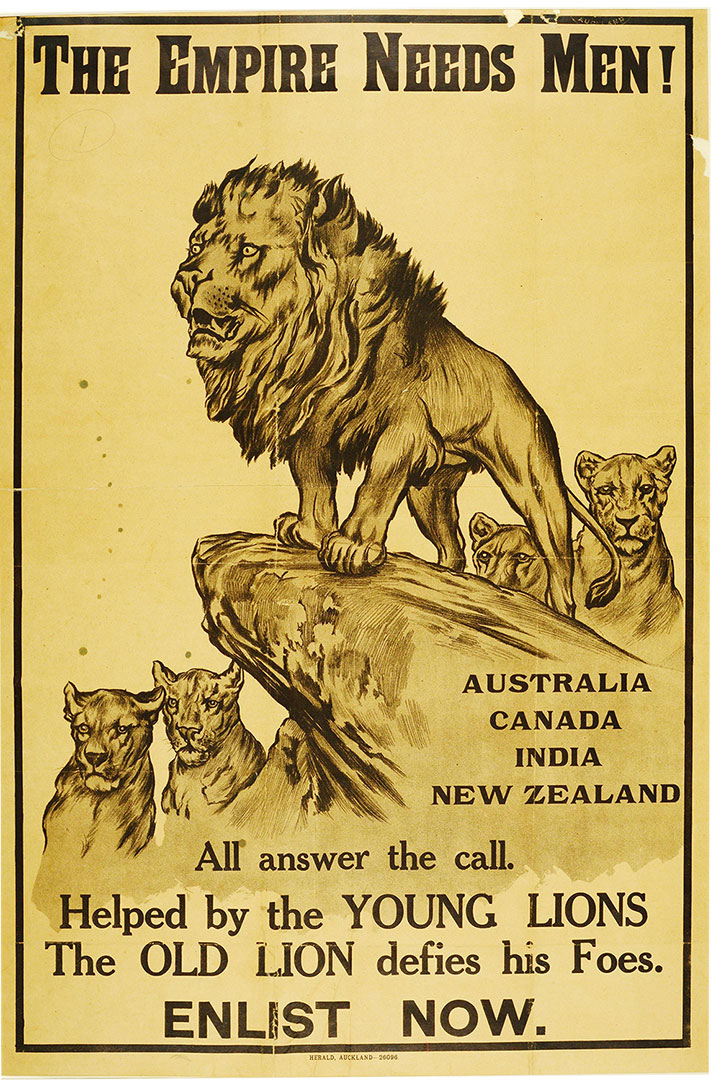

When Great Britain first applied for membership to the EEC in 1961, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders were shocked. Their ‘mother country’s’ turn towards Europe threatened them in many ways. On the one hand, Great Britain represented each of these countries’ largest economic market, and new potential new barriers to trade were seen as a threat. On the other, the move shook the former dominions’ cultural identity and self-image, generating a fundamental insecurity: had their British ‘mother country’ lost interest in its imperial family? The situation at British airports in the early 1970’s exemplified the anger, disappointment, and disbelief felt by Australians, Canadians and New Zealanders at the new system of order: while Europeans were now allowed to enter Britain easily, they now had to wait in a queue along with other international travellers reserved for foreigners. At the same time, some people saw the situation as a positive development. Younger people in particular, as well indigenous groups and self-identified nationalists, did not see Britain’s withdrawal as a threat, but rather as an opportunity to find and develop their own identity independent of Britain and the Empire.

(From: Observer, 10.06.1962)